The rapidly expanding Corps of Engineers, activated the 340th Regiment at Vancouver Barracks in March of 1942, ‘seeding it’ with a small cadre of officers from the 18th Combat Engineer Regiment. On March 9, sixty-two enlisted men from Fort Francis E. Warren joined them and in short order several hundred more arrived from Fort Leonard Wood. By April 1 Colonel Russell Lyons, their commander, had a full complement of officers and men, and the 340th was already loading supplies and what equipment they had for shipment north. On April 18, the bulk of the 340th left for the North Country — by train and then by ship (USS St. Mihiel ). Six days later they docked at Skagway, Alaska. On the 23rd, the balance of the regiment, 10 officiers and 343 enlisted men hurried to catch up. Travelling by rail to Prince Rupert, BC and sailing on the SS Prince George, they steamed up the inside passage and arrive in Skagway on the 24th, just one day behind.

The North Country offered but one route from the ocean into Yukon, Territory–trains on the narrow gauge WP&YT (White Pass and Yukon Territory) railroad climbed abruptly from sea level onto the coastal mountain range, clung precariously to the cliffs that bordered Lake Bennett to the narrows at Carcross then made its way on to the territorial capital–Whitehorse.

The 18th regiment had arrived in early April and moved immediately on to Whitehorse. But the 93rd arrived in Skagway a week before the 340th, and the two regiments jammed the tiny city. Slated to build road in the Yukon interior, from mile 0 on Nisutlin Bay, at the end of Teslin Lake, southwest across the Continental Divide to Lower Post, the 340th and its commanders faced an immediate challenge–how to get themselves and the heavy equipment they hoped would arrive soon, through the rugged country to their base camp at Morley Bay and their starting point at Nisutlin. The plan to meet that challenge was complicated to say the least.

At the end of April, Company D and the H&S Company of the 340th took the WP&YT over the White Pass and on to Whitehorse, ordered to be ready to move by steamer up the Yukon River then back down the Teslin River to Teslin Lake and, finally, Morley Bay–as soon as the ice broke up on the route. The balance of the regiment waited in Skagway, upgrading the road to Dyea at the foot of the famous Chilkoot Pass, improving sidewalks and streets and even helping the local ladies plant flowers. They waited while the 93rd Engineers built a 73 mile supply road for them to march over–from Carcross to the Teslin River–so they could travel the river from there on to their new home at Morley Bay.

General William Hoge, Commander of the Northern Sector, conceived and ordered the plan and it’s difficult to understand his reasoning. Why keep the 340th in Skagway planting flowers and working on Dyea Road while the 93rd moved out to build a road for them? Why not simple send the 340th to build as they went? It is at the very least, a good guess that the General and his staff preferred to keep the white regiment in Skagway and get the black one out into the interior as soon as possible. Since both the 340th and the 93rd were waiting for heavy equipment that was still enmeshed in a frantic traffic jam at the Seattle docks, the speed with which they moved themselves into the Yukon was, for the time being, of secondary importance. At the end of May, the ice finally broke. Company F stationed platoons at Skagway and Whitehorse to keep men and equipment moving and at Morley Bay to get them settled. Companies D and H&S in Whitehorse moved to Morley Bay.

Back in Skagway, the rest of the regiment had to endure some excitement before they got away. When the Japanese attacked Dutch Harbor on June 3 and 4, the news reverberated through the Alaska Command and on to the Yukon. Nobody knew what might come next. The soldiers of the 340th, waiting in Skagway, had a memorable night–on alert, ordered to evacuate civilians and defend the city if necessary–and very aware that, while they had rifles aplenty, they had not even a token amount of ammunition. The Japanese did not attack up the Inland Passage, the 93rd completed the supply road and the 340th finally reunited at Morley Bay by June 18. On that day, Lyons sent reconnaissance, with a detachment of the attached 29th surveyors, up the Morley River, found a route and finally began making road–with picks and shovels and hand saws. The heavy equipment was still lost somewhere far behind them.

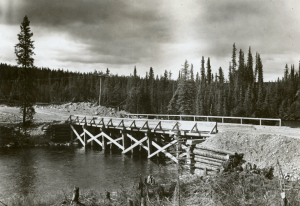

By July 1 they had five D8 Bulldozers. By the middle of the month they had nine more. But at that point they had only built 15 miles of Pioneer Road, and it was obvious to Hoge that they couldn’t possibly make Lower Post on schedule. At this point the planning got serious. Hoge ordered Lyons to forget about Pioneer Road standards, to settle for a single track road in the interest of speed. And he ordered the 93rd to fall in behind them. Starting at mile 15, the 93rd would widen and grade the road, construct and reconstruct bridges, install culverts–bringing the 340th single track road up to Pioneer Road Standards. By the end of August the 340th was at the Upper Rancheria River and the 93rd wasn’t far behind them at Swan Lake. The schedule called for the 340th to make Lower Post by mid-September. That would have them back on schedule and, with the 93rd upgrading behind them, they would be free to push on into the Southern Sector–building, once again, to Pioneer Road standards.

With any luck, the 340th would meet the 35th Engineers, working up from the South by the end of September. In fact, the lead Cat of the 340th broke through to Watson Lake on September 3. Clearly things were looking up, and Hoge modified the plan once more. He ordered Lyons to split his regiment, sending one battalion on south to link with the 35th, turning the other around and sending it back toward the 93rd, upgrading as they went.

The northbound 1st Battalion upgraded the trail from Watson Lake at mile 285 to the second Rancheria River crossing at mile 235. The Southbound 2nd Battalion linked with the 35th at Contact Creek on September 24. Their main mission accomplished, the 340th scattered from Judas Creek to Delta doing whatever needed doing. Company E contributed to the, ultimately, abortive effort to build the Canol Road. Their fellows maintained stream and river crossings between Whitehorse and Fairbanks and drove the Fairbanks Freight trucks. In March of 1943, the 340th began to reassemble. Ultimately they returned to Skagway, shipped to Prince Rupert and travelled by rail to Camp Sutton, North Carolina. They were home in September of 1943.