The armed services of the United States expanded as fast as possible during the late 1930’s and early 1940’s. Few among the country’s civilian and military leaders doubted that war was imminent. Among thousands and then tens of thousands of new recruits who poured into the Army were thousands of black men, and they presented special problems. Black Soldiers had been part of the army since Civil War times, serving in segregated units, typically commanded by white officers. New black troops would serve in similar units.

Furthermore, the officer corps all but unanimously assumed that black troops were inferior. Black regiments would be “general service”, organized to provide unskilled labor in support of their betters.

Shortly after Pearl Harbor, when it became obvious that defense against the Japanese required a land route to Alaska, building that route became the Corps of Engineers most urgent priority. And building 1500 miles of pioneer road through some of the most difficult climate and terrain in the world was going to take a lot of engineers–seven regiments. This was exactly three more regiments than the Corps had available.

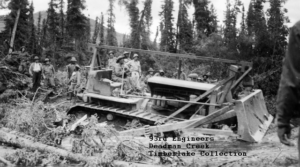

So they organized and manned three general service regiments. All were black regiments. During eight incredible months in 1942, courageous, dedicated ordinary men built an extraordinary road. The effort demanded every ounce they had to give and, white or black, they all gave it. The only difference was the amount of credit the corps, the army and the early historians of the road gave back to the black men. And that difference was grotesquely unfair. For decades the men of the three black regiments that conquered mud, mosquitoes and mountains to push the ALCAN through were ghosts. No one knew they were there. The 93rd Engineering Regiment was the least visible regiment of them all.

A small cadre of white officers and black NCO’s, commanded by Lt. Col. John Zajicek, ‘became’ the 93rd Engineering Battalion at Camp Livingston, Louisiana in February of 1941. The first large group of new inductees joined them in April. Zajicek had never commanded black troops, and, given the attitudes of his time, it’s doubtful that he considered his new command a great career opportunity.

Of the officers in the original cadre of the 93rd, First Lt. Robert P. Boyd who became and remained commander of Company C became especially important years after the Corp left the Yukon. His memoir–Me and Company C–was, and is, one of the few sources of information about the history of the 93rd. The cadre did their best to turn the flood of new recruits into soldiers–and engineers.

And they succeeded well enough that the Battalion played an important part in the Texas-Louisiana Maneuvers during the late summer and fall of 1941. The 93rd established water points, built and repaired road and bridges, constructed POW facilities…They also blew up bridges and received a letter of commendation for their successful demolition activities. The only black officer in the 93rd came to them in October of 1941. First Lt. Finis H. Austin served as regimental chaplain–and spokesman for the black enlisted men–throughout their time in the Yukon.

In November, when Zajicek fell ill and transferred out, Capt. Arthur Jacoby took command of the battalion. And in the first week of April 1942, the wave of decisions in far off Washington rolled over Jacoby and his battalion. On the 6th they were ordered to transform themselves into a general service regiment and on the 7th they received orders to prepare for immediate overseas duty. It would fall to Jacoby to lead them through the early stages of their reorganization as a regiment–even as he led them to the North Country. And an advance party under First Lt. Frank R. Holtzapple entrained for Prince Rupert, British Columbia the very day their travel orders arrived.

Five days later the rest of the regiment loaded their heavy equipment and their confused selves aboard the Rock Island Railroad and followed. Holtzapple’s detachment transferred from railroad to SS Princes Louise in Prince Rupert and made their way directly to Skagway, Alaska. The rest of the regiment paused at Camp Murray, Washington just long enough to receive their new regimental commander–Colonel Frank M Johnson (Jacoby, promoted to major and became Johnson’s Exec).

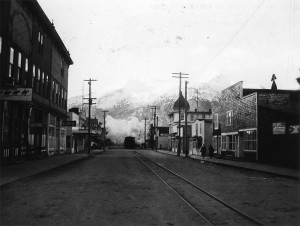

From Camp Murray the still organizing 93rd made their way north in three groups. First away, Company C and part of Company D followed the route of the advance party by rail to Prince Rupert and by luxury liner SS Prince George to Skagway. Company E and the remainder of D sailed directly from Seattle to Skagway on the SS Princess Louise. Headquarters and the rest of the regiment followed them on SS Columbia. By April 24th Col Johnson had his regiment in bivouac at the airfield in Skagway and was finally free to set about organizing them into a functioning team. The regiment was headed for Carcross, Yukon Territory and the only was there was the primitive, narrow gauge railway – The White Pass and Yukon Territory Railroad (WP&YT).

It took until May 10 to get the entire regiment to Carcross. And their heavy equipment hadn’t arrived yet. Undaunted, Johnson, who a few weeks earlier had started organizing by meeting with his junior officers and NCO’s in a Skagway schoolhouse, now sent his battalions out to make do with what they had.

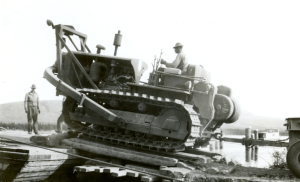

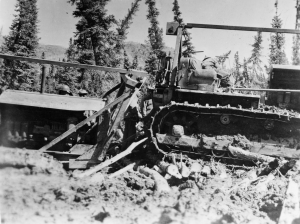

The 93rd set to work with hand tools and two borrowed dozers. The fate of the 93rd in Canada was inextricably bound up with that of the 340th Engineers. The 340th was tasked with building the highway from Nisutlin Bay over the Continental Divide and on to Lower Post where they would connect with the 35th Engineers, building north from Ft. Nelson in British Columbia.

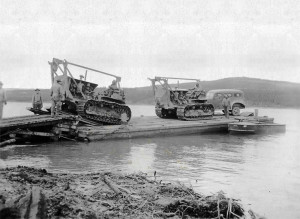

But Nisutlin Bay lay far in the interior, so the problem facing the commander of the Northern Sector, Brigadier General Hoge, was getting them there. His plan was to send half of the 340th to Whitehorse and carry them on boats via the Yukon River, the Teslin River and Lake Teslin to Morley Bay, their new home. But on May 1st that route was still locked in ice. That half of the 340th would have to wait several weeks.

The rest of the 340th, he proposed to transport to Carcross via the WP&YT and then travel 73 miles over a supply road from Carcross to Teslin River. The men would board barges or sternwheelers and float south to Morley Bay.

The problem with that plan was that there was no supply road between Carcross and Teslin River. Hoge’s answer to that was to send the 93rd to Carcross immediately and have them build one. Why he didn’t simply send the 340th to Carcross and have them build the road as they went, is not immediately clear.

But one suspects that it had to do with the fact that the 340th was a white regiment. Somebody was going to spend several weeks in Skagway, waiting for the road. Whoever that was would be as useful as possible, but they would be basically, killing time in close company with the citizens of Skagway.

The white men of the 340th stayed in Skagway and the black men of the 93rd headed for Carcross. Their first and very urgent mission was to construct the supply road for the 340th –Carcross to Teslin River. They built that 73 miles of road in exactly one month and 12 days. They pushed 23 miles to Tagish by June 4. The blew by Jakes Corner at mile 33 and by June 17 they were on Squanga Lake at Johnson’s Crossing. A battalion of the 340th marched and drove over that road to join their fellows in camp at Morley Bay (adjacent to their starting point at Nisutlin Bay). And their official history describes that trip. It makes no mention of the 93rd.

From Johnson’s Crossing, some of the 93rd moved back to Jakes Corner and started a connecting road that would run northwest to the M’Clintock River and on to Whitehorse. The rest kept building south and east to the location on Nisutlin Bay where the 340th had started their construction eastward toward Lower Post. Getting the 340th to Nisutlin Bay had taken significantly longer than Hoge had planned. Worse, their heavy equipment took even longer. By mid-July their D8’s were finally arriving, but they’d only built 15 miles of highway. They were clearly not going to be at Lower Post anywhere close to on schedule.

Hoge changed his plan–and the mission of the 93rd. He ordered the 340th to forget about Pioneer Road standards after mile 15, to build a single lane path through the wilderness just as fast as they could. And he turned the 93rd around to follow them south, reconstructing bridges, building bridges, installing culverts, grading and widening the road. The 93rd would convert the rough trail to a Pioneer Road. The PRA would complete the road to Whitehorse.

By August 10th the 93rd had completed 100 miles of road to Teslin Village at Nisutlin Bay. Crossing the bay they fell in behind the 340th. The First Battalion did final grading, Company D and Company F laid ‘corduroy’ and spread gravel. In late September, his schedule restored, Hoge modified his plan again. He split the 340th, sending half on to meet the 35th and turning the rest back toward the oncoming 93rd, upgrading their own road as they went.

By October 16, the 93rd had not only upgraded miles of road but also built culverts and four bridges. And the pioneer road connected Whitehorse to Carcross and Carcross to Teslin River, Teslin, Lower Post and beyond. Colonel Johnsons’s farewell letter presented the statistics of accomplishment. Between June 5 and October 1, the 93rd built 240 miles of road through mountains and deep canyons and muskeg swamps and mud.

Chief Engineer Corps General Sturdevant later called it the best stretch of road on the highway. The official history of the 340th lavishes loving attention on their highway building from Nisutlin Bay to Lower Post. And the contribution of the 93rd is, again, ignored. Through October and early November, the regiment scattered to do a number of “end of the project” jobs. They built barracks, relay stations and installed drainage stations. One platoon ran a sawmill at mile post 204. A detachment from Company C actually began work on the ill-fated Canol Road that the Corps expected to connect Johnsons Crossing to the oil well at Norman Wells.

On October 18, Col. Frank Johnson transferred to command the 18th Engineers and Lt. Col. Walter Hodge assumed command of the 93rd. Hodge immediately began planning to move the regiment to winter quarters at Chilkoot Barracks. But the move took time to organize and implement extended well into a frigid Yukon December. The 93rd found itself spread throughout Yukon territory from Judith Creek, Robinson, Whitehorse, Squanga Lake and back to Carcross.

Operations of the 93rd Regiment in Yukon Territory officially terminated on December 10, 1942. And on Christmas Day the 93rd sailed to Chilkoot Barracks in Haines, Alaska. From Chilkoot the regiment was aimed at a new assignment in the Aleutians, so on Christmas day, 1942 their successful assault on the Yukon came to an end.